Urbanization

Urbanization

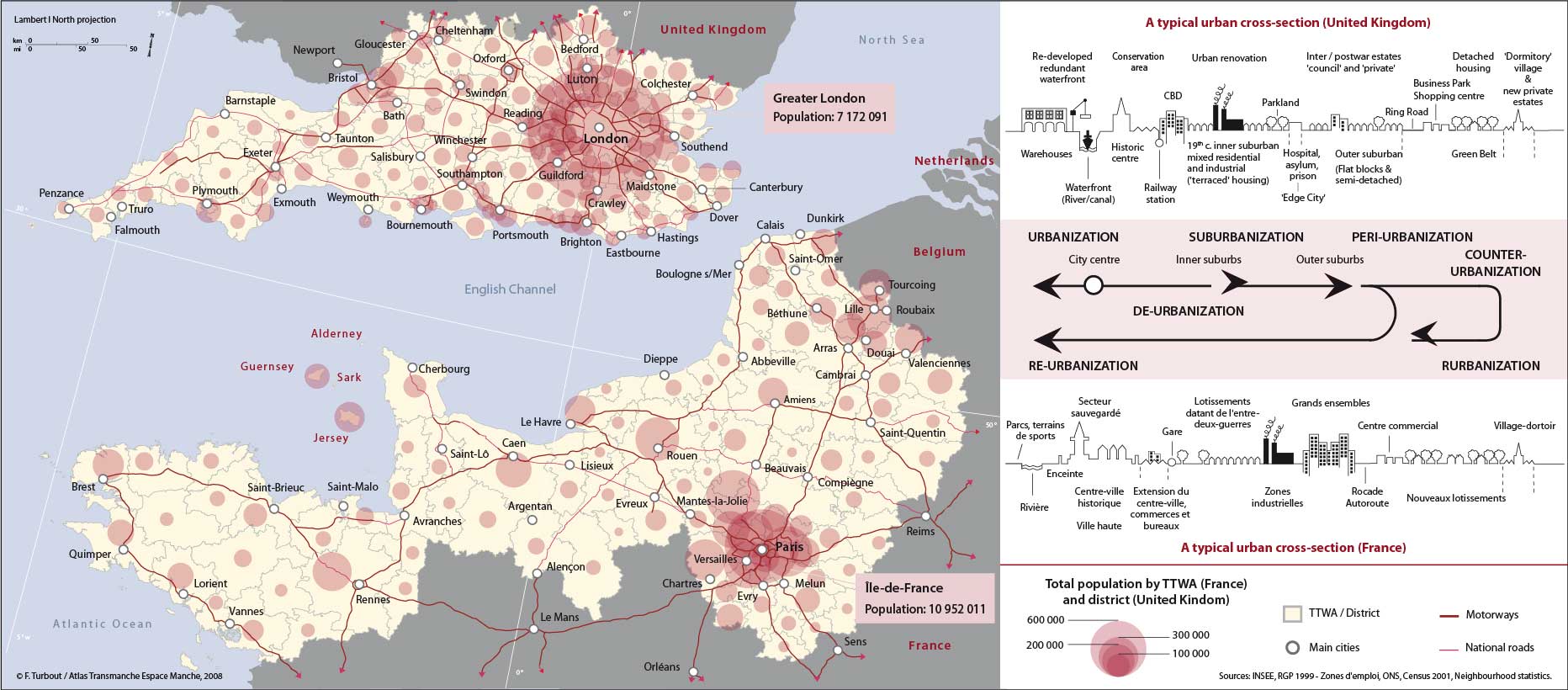

Across the Channel area, unequally urbanised, regional contrasts are as much north-south in direction as east-west. The English side boasts a much higher population, in absolute and relative terms. The agglomerations are greater in number and closer in their proximity to one another, and account for a higher proportion of the total population than their French counterparts. Simultaneously, the pre-eminence of London and of the spread of residential and tourist nebula along the south coast on the English side, and the weight of Paris, combined with that of the agglomerations of Nord-Pas-de-Calais, on the French side, contrasts with the progressive reduction of the urban imprint towards the west.

The degrees of similarity are, however, undeniable in terms of the many coastal agglomerations: ports, whether for commerce or passengers, fishing or military, seaside resorts, each often has its twin on the other side, to the point of evoking a sense of family link.

On both sides, the urban frame is above all dominated by the two capitals, the continent's only global cities whose size, economic power, international role and influence are without equal within the rest of the network. The extent of catchment area beyond immediate administrative boundaries, the size of employed population, the diversity of jobs market and the intensity of daily commuting flows of these two megapoles make them the central hubs of the Channel region. One like the other shows a net migration gain in respect of higher education students, and those already in work placement training, but a net loss for families due to the high costs of renting or purchasing accommodation. Both are globally important airport hubs and enjoy high connectivity being at the centres of convergence of major communication axes, reinforced by their control over decision – making in both the public and private sectors, by their extensive peri-urbanisation and their respective attraction for both tourists and second homes. Their mutual links have intensified as space-time compression brings them closer together.

The wider regional contexts are, however, different. London is well integrated within the European megalopolitan axis – the so-called “blue banana,” and as a consequence is encircled at no great distance by a myriad of closely-spaced towns, an urban network only found in the extreme north of France, the latter itself part of the dorsal population axis as seen in the presence of its conurbations (Lille, Roubaix, Tourcoing and Douai, Lens…), and characterised as the “Rhine Model.” The “Paris model” of urban spatial organisation, in contrast, sees neighbouring urban poles much further removed within the region. The ‘Polynet' research programme, developed in the context of the North West Europe Interreg B project has demonstrated the opposition which exists between a polycentric, greater southeast England and a monocentric Paris region, based on the mapping of different flows (daily commuting, telephone and postal links…). Overlap between travel-to-work areas on the English side is such as to suggest that the eastern half forms a single labour market, possibly foreshadowing a unified employment zone. Nothing comparable exists on the French side, by reason of the massive convergence of flows towards Paris, albeit increasingly divided into sub-regional catchment areas; but globally unipolar at the scale of the region in question. The employment catchment areas of the provinces have thereby retained their autonomy.

Also different is the distribution of employment sub-sectors. At the same time as Paris continues to absorb design and state-of-the-art industries, the London Basin nurtures research and innovation centres located in its medium-sized, sometimes even small towns. The correlation between employment qualifications and size of settlement is not found to the same extent in France.

The many centres of settlement within the greater southeast region are not only the product of England's early industrialisation and urbanisation, but also the result of an older deconcentration, both spontaneous and planned. Launched at the time of the ‘garden-cities', regulated by the creation of the green belt and the new and ‘expanded' towns, this trend towards ex-urbanisation was reinforced by a period of de-urbanisation, as the population of London declined to the benefit of its expanding outer periphery. This process was accentuated by a marked preference in the housing market for single dwellings, which explains the residential spread well into rural areas. The French capital has not extended as far within the Paris Basin, with its larger new towns integrated around existing built-up areas, while the absence of a green belt has encouraged an oil-stain like suburban sprawl. This helps to explain the paradox that makes Paris the largest agglomeration within the Channel region, while the total urban population on the French side is much smaller.

Most English agglomerations of a certain size have a green belt, and have been experiencing inner city population decline as a result of the ex-urbanisation process. In France, towns witnessed a much later peri-urbanisation, none of which have so far registered a sufficient decline of their population as to warrant talk of de-urbanisation. Just a few port and industrial towns are experiencing low, and sometimes negative, demographic growth.

The various stages in a cyclical model of urban change are well documented, similarly the regional variation across western Europe, and not least between France and Britain. Different cultural and economic histories have impacted on the resulting urban configurations in relation to, for example, public and private housing, and the problems of social polarisation. While urban models have sought to suggest a contrasting social and lifestyle gradient from inner to outer city, based on class and income, in both countries, with the more marginalised sections of society clustered around the central city area in Britain, and much further removed into the suburbs in France, the reality today is sometimes very different. Signs of ‘re-urbanisation' in Britain are well established. Urban decline itself has engendered profitable opportunities in the inner city, where the redevelopment of redundant warehouses and wharf waterfront areas has led rapidly to gentrification and social change. Boosting the image of the central area has become a matter of urban survival.

top