Culture - Heritage

Culture - Heritage

The impulse to preserve landscapes and buildings from the past is peculiarly European. Living in an “old country,” it is perhaps only to be expected that the conservation ethic remains strong, particularly when parts of a nation's heritage are threatened. The growing impact of uncontrolled development and industrialisation in 19th century England prompted three Victorian philanthropists to set up the National Trust in 1895 to act as “a guardian for the nation” in the acquisition and protection of countryside and buildings at risk. More than a century later, some 250 000 he. of beautiful countryside and nearly 200 historic houses and castles are held in perpetuity, the vast majority open to the public and attracting around 13 million visitors each year.

In respect of urban heritage, the French and British approaches to both preservation and conservation follow broadly the same lines, with origins often traced back to the destruction of monuments of particular historic importance. A grave loss for France came in the aftermath of the Revolution, with the destruction of the great Abbey Church of Cluny, an outstanding example of Romanesque art. Both countries today have a panoply of statutory instruments which date back into the 19th century, but France, through its Direction de l'Architecture, retains far more centralised control than Britain. The French system of “classement” dating from 1913 corresponds to the English “listing” (or “scheduling”) that was not introduced until 1944. Given France's rich heritage of historic buildings, surprisingly lower numbers are “classés” or “inscrits” than in the UK's three-fold system. However, in both French categories, restrictions cover not only the building or land but also the surrounding area up to 500 m, the “zone protégée.”

The “Malraux Act” followed on logically in 1962, aiming at protecting whole urban areas as “secteurs sauvegardés,” five years ahead of its UK counterpart, “conservation areas,” sanctioned by the “Civic Amenities Act” of 1967. Whole areas of historic architectural importance had increasingly come under threat from rapid urban re-development in the postwar years. Inevitably, the higher cost of restoration as opposed to new build and the social impact of the resulting “gentrification” were much debated. In small historic towns like Chichester (a veritable museum-piece of urban history within its almost intact Roman walls), the outcome was never in doubt. In larger port cities like Southampton and Cherbourg, already in part war-damaged, the decisions were much less predictable. Their two “Art Deco” ocean terminal buildings recalled the glorious inter-war years of the trans-Atlantic liner crossings. The Southampton Ocean Terminal, home of the “Queens,” was unceremoniously demolished in 1983, whilst its counterpart in Cherbourg, magnificently restored after massive damage during the German retreat of 1944, was threatened by complete demolition in the late 1980s. Listed as a “monument classé” in 1989, the “Gare Maritime” today houses the culturo-museum complex of the “Cité de la Mer,” with the elegant period design of the former baggage hall providing a backdrop to the exhibitions of past emigrations from Europe to the New World.

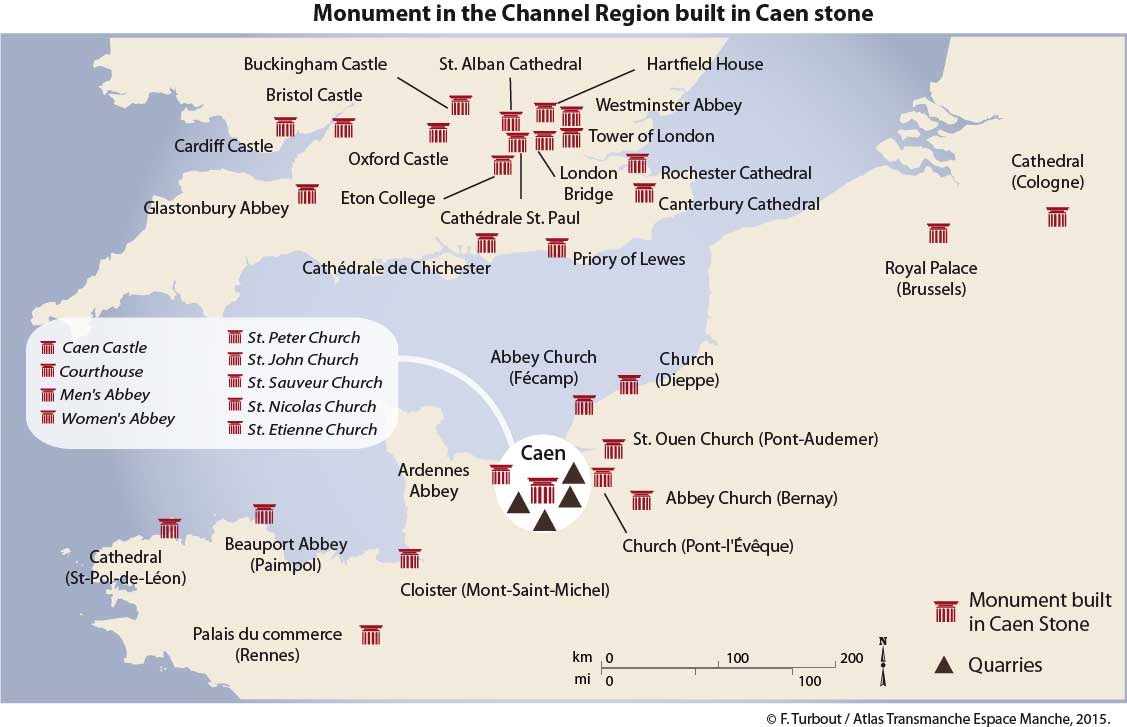

Well into the 20th century cities, as custodians of Europe's cultural patrimony, would find themselves protected as never before, particularly with regard to the masterpieces of the medieval period. Southern England and Northern France boast some of the most acclaimed religious and secular architecture of the last millennium. National history which all too often shapes views of the past was, for a time, transcended in the Anglo-Norman Kingdom of the 11th and 12th centuries. The cathedrals, abbeys and castles have been described as forming a “stone chain” that bound together the Norman provinces on either side of the Channel. The architectural fulfilment of what had been initiated at Jumièges and Caen in the mid-11th century is to be found at Winchester, Rochester and Canterbury. Even the limestone used for building was imported by barge from quarries in Normandy! The Norman style, as the early Romanesque is known in England, would evolve into early Gothic; the massive wall structure and frontality enclosed by flat wooden ceilings was eliminated in favour of a lighter structure with rib vaulting, while pointed arches and slender columns emphasised soaring space and verticality. The student of one of the great high points of religious architecture in Medieval Europe is overwhelmed by the embarrassment of riches to be found inland from the two facing coastlines.

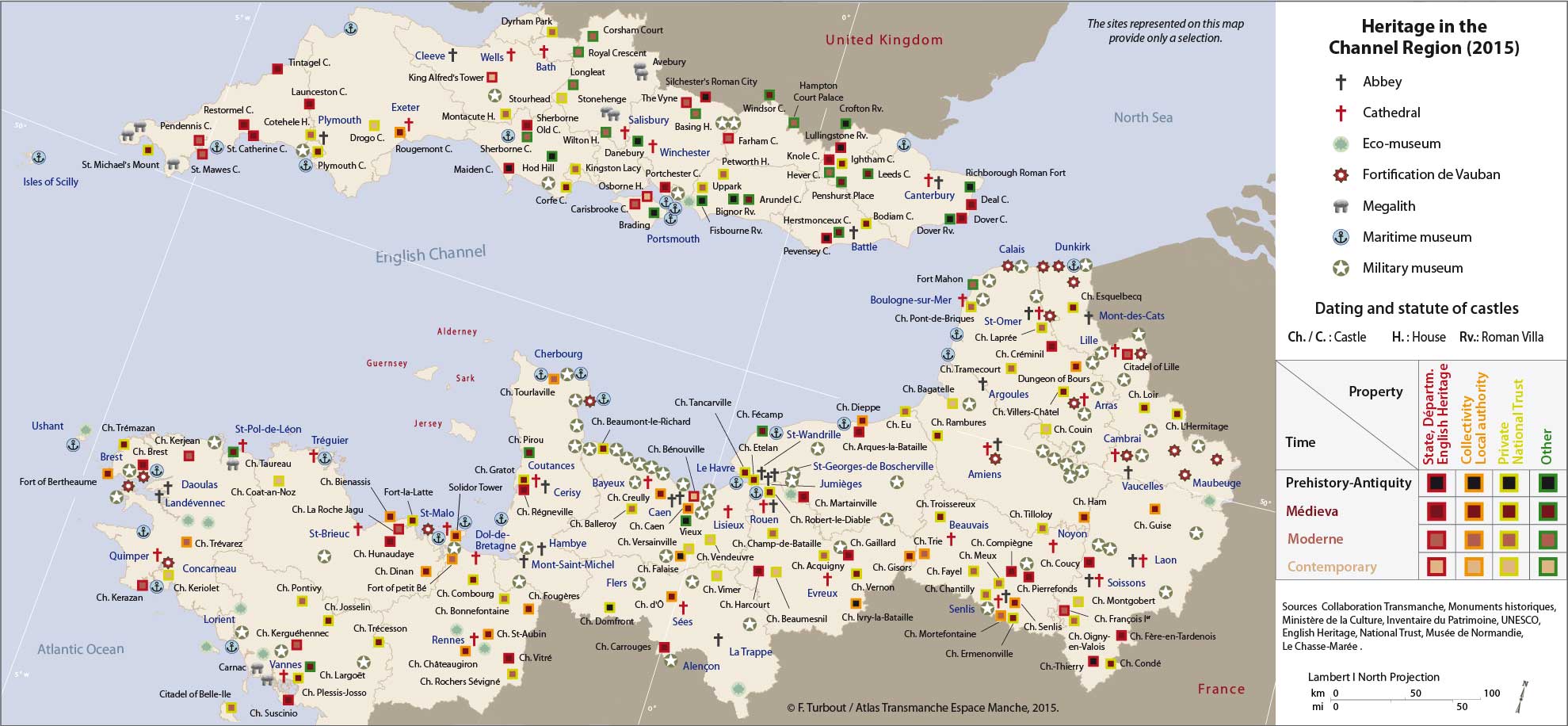

The most prominent heritage associated with the coasts of the Channel (apart from their evident scenic beauty) is the large number of defensive fortifications. Under Henry VIII, England saw the emergence of the first truly national system of coastal defences, prompted initially by the threat of invasion from mainland Europe. Some 18 large forts were built along the Southern English coast between 1539 and 1543. Further reinforcement would follow in the reign of Elizabeth I, but mainly in southwest England due to the Spanish threat. A century later, with an Anglo-Dutch alliance pitted against the French in the Channel, Vauban was fortifying the whole length of the northern coast. These massive stone sentinels, clustered particularly around Brest, St. Malo, Barfleur/St-Vaast-la-Hougue and Pas-de-Calais, were, of course, only a part of a huge programme of fortifications encircling France, a rich military heritage of some 160 forts and citadels, recently celebrated in 2007 on the 300th anniversary of the death of Louis XIV's great Maréchal de France.

The era of Vauban would prove only to be a prelude to a further century of almost continuous hostility between France and Britain through to the Napoleonic Wars. Even after the coming to power of Napoleon III, with the enlargement and fortification of Cherbourg harbour, the fears of invasion persisted. In the event, there was no invasion, but Palmerston's “Follies,” a line of great fortresses built in the 1860s around the main English dockyard towns and naval bases, remain a prominent testimony to military engineering skills. In terms of national heritage, they are acknowledged as important structures, progressively being opened to the public and interpreted as tourist sites, as at Plymouth, Portsmouth and, most recently, Newhaven. However, the abundance of such military heritage in the cross-Channel region has brought its own problems in terms of generating new uses and meanings. Of the 52 historic forts surrounding Portsmouth on both land and sea, 20 are museums, 13 are devoted to leisure or recreational activities, 6 are still used by the Ministry of Defence, 3 are re-used as industrial premises, 2 are residential and the rest are either derelict or demolished. Whether in private or public ownership, the problem on both sides of the Channel has been costly upkeep and maintenance. Where attempts have been made at interpretation, all too often the focus on the edifice itself, i.e. the “hardware” for the public gaze, has relegated the “software” aspect - the impalpable association with the associated historic events. In England, in order to access additional financial support from the Heritage Lottery Fund (created in 1994 out of the profits of the National Lottery), the success of any development bid relating to an historic landmark, building or museum is dependent on demonstrating a strong educational dimension, as well as objectives relating to social inclusion and sustainability.

Between the first line of defence (the navy) and the second line of defence (the coastal fortifications), lay another world of fishing ports and commercial harbours that gave life and sustenance to maritime communities. At a time when this traditional face of the maritime economy has come increasingly under threat, sailing and power-boat cruising have experienced quite unprecedented growth as leisure activities, spawning a new wave of interest in the world of the sea. The French have coined the word “maritimité” as evocative of this new attachment, which geographically is most associated with Brittany. It was this region that campaigned for the Département de Monuments Historiques to create a register of “listed” vessels in 1983, very much along the lines of the Historic Ships Register in the UK.

Recalling the past and recreating it has in recent decades seen the building of full-size “authentic” replicas of traditional sailing craft, the organisation of major “Festivals of the Sea” and the opening of both small and large maritime museums. Given the common ties linking their respective maritime histories, it is hardly surprising that all these activities are also to be found flourishing in Devon and Cornwall, with the latest landmark provided by the opening of the National Maritime Museum on the Falmouth Harbour waterfront. In most such ventures the commercial imperative remains strong. Not all would succeed as the reinterpretation of maritime culture was skewed in favour of the tourist industry. The floating museum of Port Rhu was soon in financial difficulty after opening in 1993, as was its fishing industry at that time.

Conservation of architectural heritage is undoubtedly stimulated by invoking nostalgia for the national past. The similarities in national interpretations were deliberately reinforced by co-ordinated action centred on European Architectural Heritage Year in 1975. The slogan “A future for the past” largely rearticulated aims already embraced in both the UK and France, but assumed international credence through commitments to matched funding for various pilot projects promoted by the Council of Europe. Soon after this in Britain the National Heritage Act of 1980 identified two main objectives; to ensure that the “heritage” is available for cultural consumption and to see that it is displayed as such. In 1984 a new national body, English Heritage, was created by Parliament, charged with the protection of the historic environment. It is the government's official adviser on all matters concerning heritage conservation, including the scheduling of historic buildings. It provides substantial funding for archaeology, conservation areas and the repair of listed buildings and is responsible for some 400 historic properties in the nation's care. More commercially, English Heritage also boasts the largest events programme in Europe, with spectacular battle re-enactments, colourful live history encampments, authentic mediaeval markets in a “Disneyfied” pageant of history.

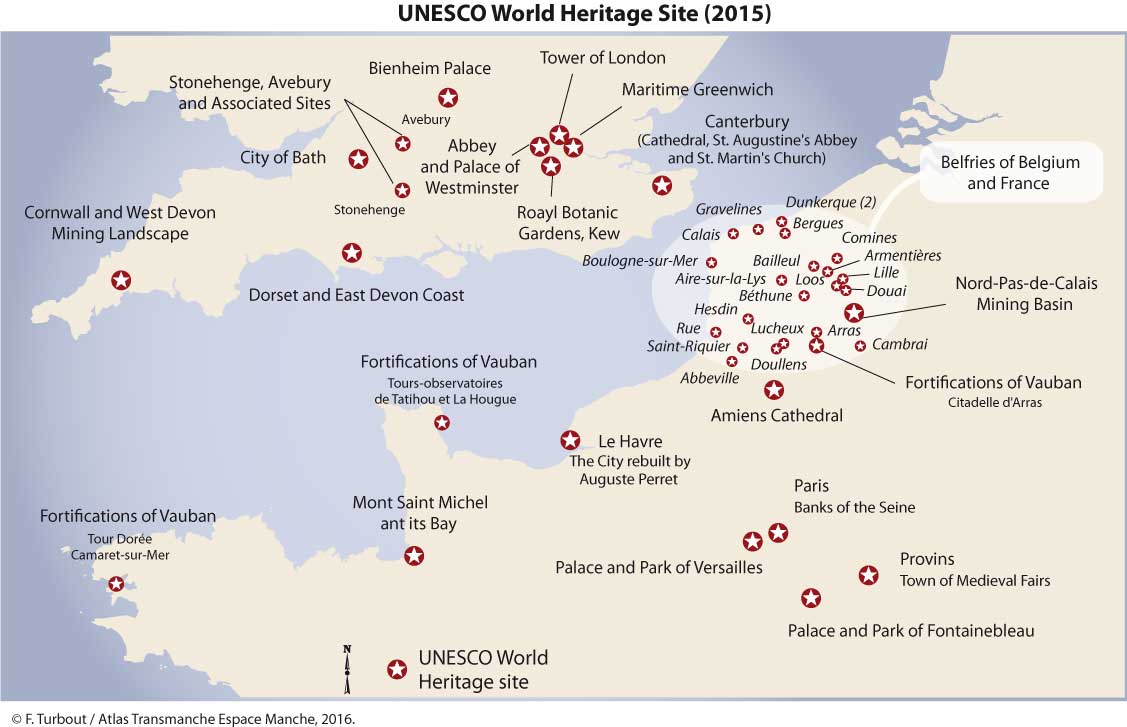

Matching the “academic” to the “popular” is seen by many as part of a challenge to recreate public history on a national scale, a re-appropriation or even re-invention of the past. Some critics of this so-called "heritage industry" see it as an attempt to re-package collective memory.UNESCO has little concern for academic niceties, and has since 1978, created its own list of both “natural” and “cultural” sites. To date, of more than 850 World Heritage Sites, the most recent to be designated in the cross-Channel region are “Cornwall and West Devons Mining Landscape” and “Nord-Pas-de-Calais Mining Basin” .

top