Tourism - Recreational boating

Tourism - Recreational boating- Le poids économique du tourisme (2018) FR

- Recreational boating (2006)

- Recreational yachting (2009-2012)

- Tourism (2005)

- Tourisme (2014) FR

The seaside resort was invented in the English Channel, and its early development on both coasts was under royal patronage. When Queen Victoria bathed for the first time in the sea in 1847, she was not the first royal bather. George III in 1789 had bathed at Weymouth to the accompaniment of a chamber orchestra, while his son, the Prince Regent, opted to favour Brighton where the fashion for seaside watering places had begun a few years earlier. Across the Channel in Dieppe, in 1822, the Duchess of Berry created the first sea-bathing establishment to introduce the ladies of “high society” to the custom. Three years later she was in Boulogne, whose status as “Queen of Seaside Towns” was confirmed by the visits of Prince Albert in 1854 and the Emperor Napoleon III in 1860. A small English colony had already grown up, the 5 000 permanent residents being joined each summer by 10 000 compatriots. With peace in the Channel after 1815, the idea of the pleasure resort, already well established, would flourish, but it would not remain the preserve of the rich and aristocratic for long on the English side. Railway access from London to the main south coast resorts was completed in the 1840s, and with it came the “trippers” on cheap day excursions, benefiting from the penny-per-mile rate imposed on the railway companies by the government. The “elite” began to seek quieter shores across the Channel or smaller coastal villages further west.

The urban morphology of the new seaside resort was dictated by its seafront. A spacious promenade would, on the English coast, boast a pier, jutting out into the sea and providing a “walk on the water.” Initially just an open deck, it evolved into a pleasure pier, typically including a bandstand, theatre and other seaside entertainments. Behind the promenade, there was usually a strip of gardens and lawns, such as those laid out in Dieppe in 1863 by the Empress Eugénie and Napoleon III, which might also enclose the grander buildings of the spa centre and, later, the casino. Set back from this sea frontage were the elegant terraces of tall villas and hotels. Further still behind, were the rows of shopping streets and lodging houses for poorer visitors. Finally, reaching inland, around and beyond the railway station were the packed rows of smaller terraced streets housing the new working population who depended for their livelihood on the fortunes of the seafront.

The rail connections from Paris to the coasts of Normandy and Picardy were completed two decades later than on the other side of the Channel, but the elegance and grandeur of many of the French resorts more than matched that of their English counterparts. In 1860 Deauville did not exist, unlike Trouville on the opposite bank of the River Touques. Built to cater for the international “smart set,” in four years the new resort emerged from the coastal marsh like some vast theatrical stage set, complete with rail-link, racecourse, casino and, behind its famous boardwalk, lines of sumptuous villas overlooking the seafront.

If the fashionable resorts up-Channel emphasised organised pleasure, further west down-Channel the generally smaller coastal resorts exuded a more tranquil, genteel image. Such was the growth of tourism in the late 19th century along the deeply embayed northern coastline of the Breton peninsula. A century on the trends largely reversed between the two ends of the Channel, one slowly going out of fashion, the other under pressure from mass tourism.

Prewar, long summer holidays had been the preserve of the well-to-do. In the 1920s, the up-Channel zone between Kent and Pas-de-Calais remained a buoyant area of tourist activity, greatly encouraged by English investment at Le Touquet and other resorts, and more generally closer ties through improved sea and air links. In 1936 the Popular Front gave French wage-earners the legal right to two weeks' paid holiday (in Britain the Holidays with Pay Act of 1938 granted just one week). The French annual holiday soon became a national institution, increased to three weeks in 1956, four in 1965 and five in 1981 (compared to the existing legal minimum of three weeks in Britain). It was hardly surprising that during the ensuing decades the proportion of the population taking an annual holiday rose significantly. Tourism fast became a major industry. Notwithstanding these general trends, the Second World War resulted in significant changes to the map of tourism in France. With postwar reconstruction along the whole coast from Normandy to Nord-Pas-de-Calais the immediate priority, the continued growth of tourism was to shift more firmly to the northwest and south of France.

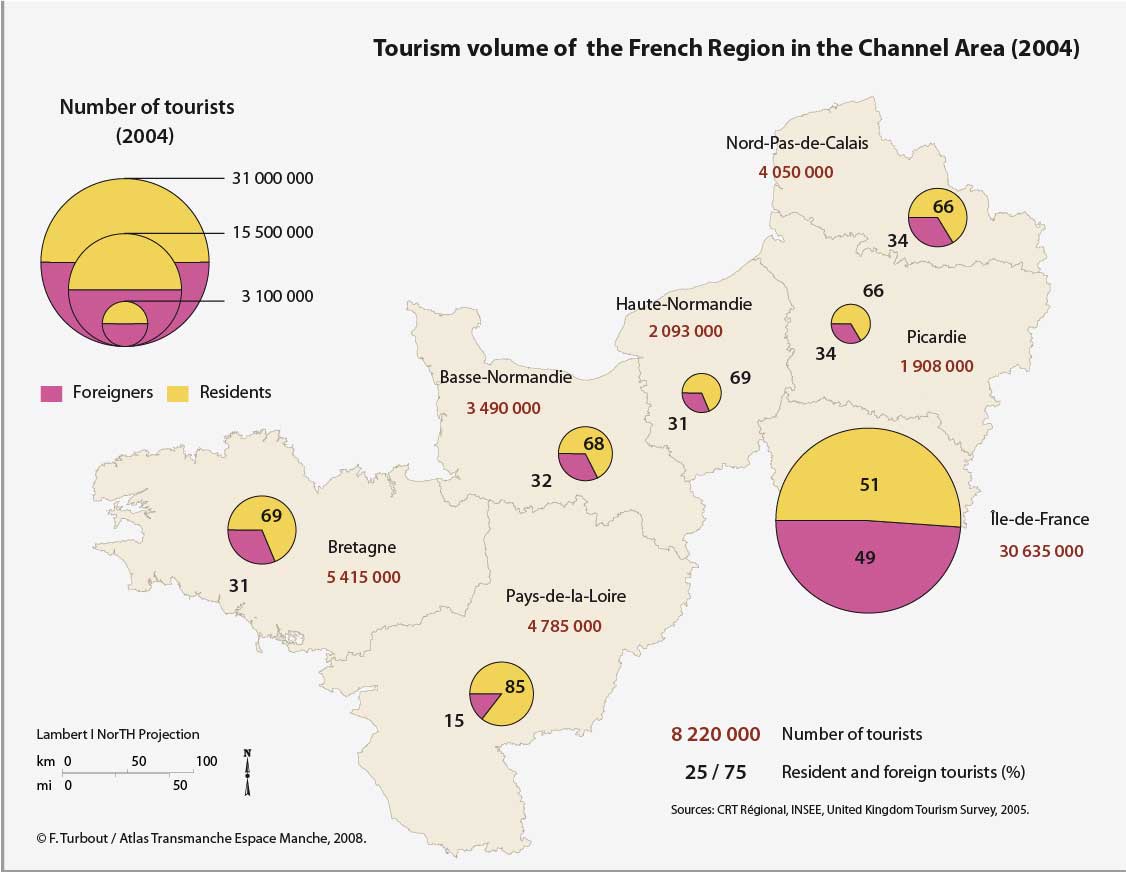

In the Breton peninsula, over 80% of tourist capacity today is concentrated along the coast; half of the accommodation capacity consists of second homes and a quarter of all tourists are foreign nationals. The almost continuous spread of second-homes and camping sites, particularly along the south coast, was the inevitable product of massive growth in the 1960s. By the 1980s, Brittany began to face problems in its tourist sector, even though it ranked as France's second most popular tourist region. Consumers were becoming increasingly differentiated and the region was failing to adapt structurally to changing demands; for too long there had been an over-dependence on the seaside summer family holiday that had caused the multiplication of small coastal resorts. Other coastal areas were beginning to compete. New golf courses, thalassotherapy centres, and other recreational facilities were put in place, but provided only a partial answer to what was clearly a change in tourist behaviour, including a shortening of the average length of stay. Interestingly, the preferred locations of British second-home purchases (around 90% of transactions) favoured parts of central Brittany and confirmed different attitudes towards tourism, already evident across the Channel in Devon and Cornwall. The emphasis on dwelling in harmony with the environment, coupled with a strong sense of traditional local identity and heritage were the very qualities that the Breton peninsula now risked losing under the impact of mass tourism.

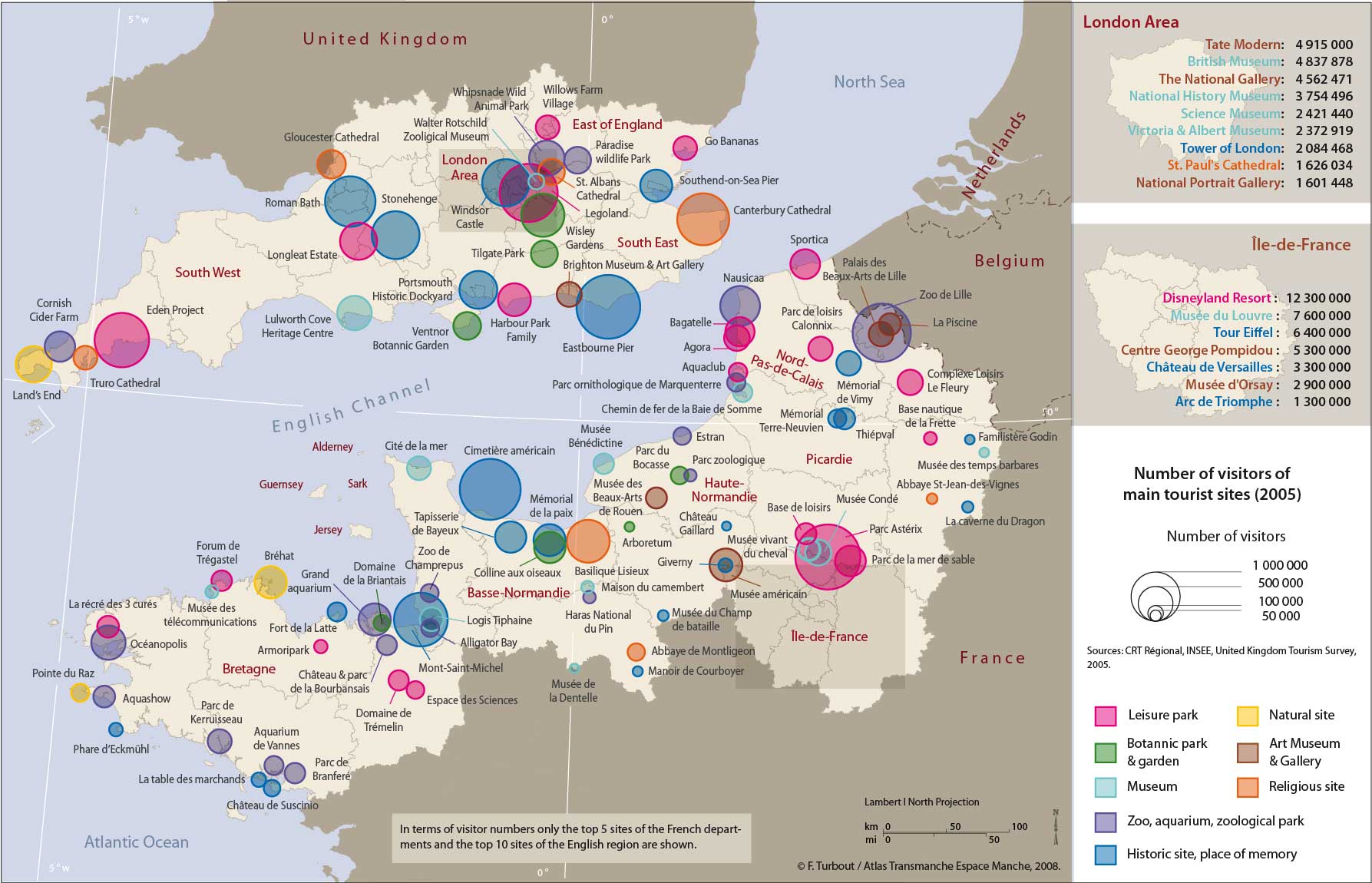

Along the southern English coast the traditional seaside resort, which had for so long claimed the loyalty of a particular social milieu, started to lose out to warmer and more exotic locations with the advent of competitively priced holiday packages in the 1970s. The cross-Channel ferry companies, faced with the opening of the Channel Tunnel in 1994, would compete with faster crossings and a wider range of routes but could not ultimately match the seemingly unlimited choice offered by low-cost airlines. Caught in a spiral of decline, the seaside resorts of Victorian England, once the source of their very own souvenir industries, now awaited the turn of the tide. Some were to persevere with new-found attractions like “Pleasure Beach” at Yarmouth; others like Bournemouth and Brighton would woo the business/conference trade, or niche market holidays for the elderly, as at Southsea. The more picturesque would attract a disproportionate number of retirees and those within easy access of London appealed to people aspiring to a second home. All could hope to benefit from the renewed vogue for day-trips and short breaks.

Tourist practices are famously fickle and subject to fashion, and on both sides of the Channel the uptake of any new tourist offer would be predicated on the variety of attractions and activities catering to a widening diversity of interests. Despite this, the most visited tourist sites reveal strong echoes of the cross-Channel region's historic role as a great maritime thoroughfare, its disputed naval history and the memories of two world wars. Recent developments of Oceanopolis, Nausicaä and Cité de la Mer take visitors' imaginations out of the Channel to the oceans beyond.

Beyond themed attractions such as the Eden Project in Cornwall, many of which have no particular place identity, there lies the continued lure of the countryside itself. The pioneers of modern

countryside recreation came out of the romantic revival, inspired by people like Rousseau and Wordsworth. Once the prerogative of the affluent minority, the growth of car ownership in the postwar

years led to a significant growth in outdoor activities well away from the cities. The multiple uses of the countryside inevitably resulted in a collision between land interests and recreational

interests. In Britain the Countryside Act of 1968 provided for hundreds of country parks with carefully integrated recreational facilities and, in most cases, accessible from major urban areas.

In France, this

reconnecting with the “rural” similarly brought about a popular new dimension to domestic recreation and tourism. The establishment of the Parc naturel régional du Nord-Pas-de-Calais - Boulonnais

in 1978, with its dramatic cliff-top headlands of Gris-Nez and Blanc-Nez, is credited as marking the tourist revival of the Côte d'Opale. This time, the trippers were not from across the

Straits but from the metropoles inland to the east. When the building of the Channel Tunnel was confirmed in 1986, this gave renewed impetus to trans-frontier co-operation across this maritime

Euro-Region. The first joint programmes to be announced were in the field of tourism.

top