Maritime Safety

Maritime Safety- Accidental marine pollution (1960-2015)

- Enjeu de sécurité (2016) FR

- Monitoring system

- Organization of maritime traffic

- Safety at stake (2007)

- Transport matières dangereuses (2008-2016) FR

On 20th January 2006, a stormy night in the approaches to the English Channel, the sea was unforgiving, the waves were steep, and the wind was fierce. The Alessia, a 95 m long Swiss freighter, built in 1999, was carrying 3 932 tons of steel from Brake in Germany en route for Haifa, in Israel, when, 38 miles north of Ushant, at 01:00 hours, it informed the CROSS that it was listing 30° to port, its cargo having shifted. At 01:40 hours, the deep-sea tug Abeille Bourbon cast off to escort the freighter following a decision by the maritime prefect, and a Super Frelon helicopter was put on stand-by. The Abeille Bourbon escorted the Alessia into the port of Brest.

Similar situations occurred eleven times in 2006 in the Corsen intervention zone that extends from Ushant to the Mont-Saint-Michel bay. Eleven escorts and four emergency tows were performed; 182 ships in difficulty were recorded, the great majority of them not serious. These numbers can be perceived as both low and high: low with regard to overall sea-rescue activity and the volume of maritime traffic; high, because we are only concerned with one section of the Channel and conditions can degenerate rapidly.

Less than 5% of the activity of the CROSS and the MRCC, the French and British organisations responsible for surveillance and security at sea, concerns merchant shipping. Most interventions involve fishing or leisure craft. Nevertheless, when account is taken of the environmental issues at stake, the size of the population affected and potential economic and political impacts, the safety of maritime traffic in the Channel poses considerable problems.

The proliferation of Channel traffic has multiplied the chance of accidents and pollution. The toxic substances transported, from hydrocarbons to chemical products, have increased in number. The condition of ships and the movement towards the use of flags of convenience, which are more lax regarding legislation, control, tax, and standards, means that the situation has become increasingly serious since the 1960s. Together these factors, particularly the intensity of traffic, have increased the level of risk in the waters of the Channel.

A traffic separation system has long delimited an in-bound lane up-Channel towards North Sea, and an out-bound lane down-Channel. The current system was preceded by a series of voluntary experiments in 1967 but it was not until 1971, after a series of accidents and 51 deaths in three collisions at the sites of partially submerged wrecks, that the authorities were forced to act. Despite this, the system only came into force definitively in 1977. The Channel Navigation Information Service (CNIS) requiring ships to comply with IMO (International Maritime Organisation) procedures when they navigate within a traffic separation system, was significantly reinforced in 2003 by the introduction of a new radar system linked to a system of information management (VTMIS). A shipping control training site was established with European funding at the MCA in Dover where the British surveillance team and its French counterpart from the Gris-Nez CROSS work together.

In the western approaches, in 2006, the Corsen logged 55 058 ships, or an average of 150 ships per day, the centre in Jobourg logged 197 per day and Gris-Nez in the Strait 163 per day. Every year, traffic increases by between 2 and 3%. Most craft are multi-purpose freighters and container ships and 20% of them carry dangerous cargoes, representing 150 million tons per year. Antigua and Barbuda, the Bahamas, Panama, Liberia and Holland are the home ports of the majority. Wherever one is at sea, the weather represents a hazard, but the approaches to the Channel, off Ushant and the Isles of Scilly, are particularly exposed. Everywhere at sea, the chance of collision has risen sharply, but it is in the Strait that it is greatest. In 2006, the Star Herdla collided with the Cape Bradley, which was carrying 30 000 tonnes of naphthalene; during the last quarter of 2006, 13 collisions, not an unusual number, occurred in the inbound lane of the Strait.

Collisions are the most frequent type of incident. For example in the Channel approaches, Jobourg recorded 103 mid-Channel in 2006, and Griz-Nez recorded 59. Contrary to popular belief, the fleet is fairly new: over 60% of craft are less than 15 years old including 21% under 5 years old.

The accidents with the most widespread consequences involve hydrocarbons; these have diminished only slightly since the wreck of the Torrey Canyon in 1967, which spread scenes of desolation along the coasts. It was not that pollution had not existed previously, but that event marked the combined onset of rising tanker size, growth in traffic, increased coastal settlement and awareness of environmental issues. More or less serious incidents followed, for example the Amoco Cadiz (1978) but they diminished in proportion to numbers of vessels, traffic having increased considerably. The Erika incident (1999) marked the beginning of increasingly powerful public and institutional reaction. Chemical tankers have also had their share of accidents (e.g. Ievoli Sun, 2000) although so far incidents involving them have been less serious. The number of loose containers has risen sharply: lost, and floating just beneath the surface, they constitute a hazard. In 2007, the managed beaching of the MSC Napoli in Lyme Bay on the Dorset coast – a UNESCO World Heritage site – showed what could happen again. For the first time, in the winter of 2007, British and French authorities banned entry into the Strait of a container ship coming from the North Sea. Battered by a violent storm it constituted a danger. This situation illustrates both the new risks that are arising and the responses taken to meet them.

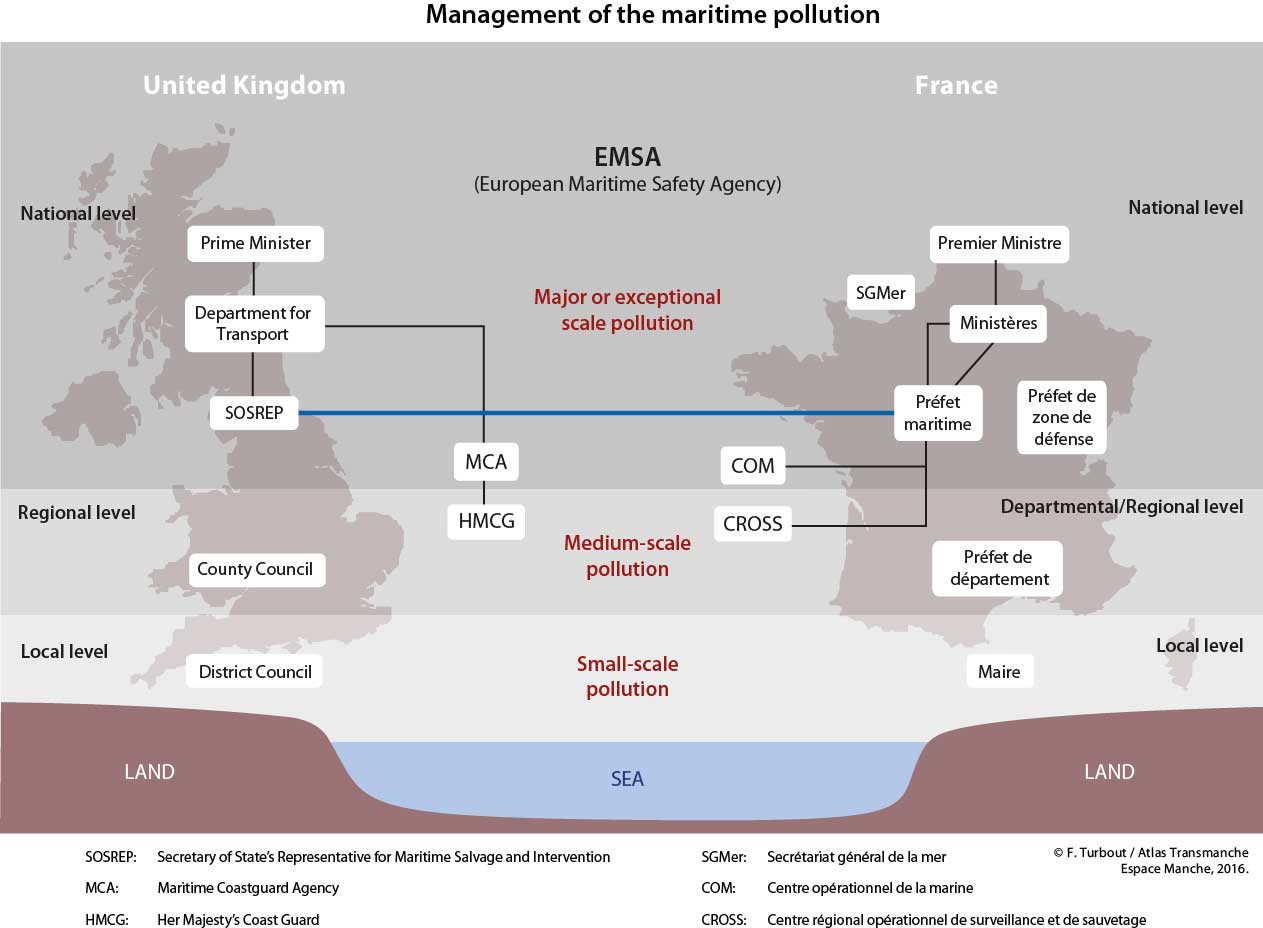

Maritime safety is a complex domain and is organised at several levels. International law, as set out by the Montego Bay agreement, applies everywhere and derives from several different conventions, starting with Brussels (1913), Montego Bay (1948), through to those most recently adopted under the aegis of the IMO in partnership with the UN. To the laws of the coastal states can be added the emergence of European Union policy and regulations. The Channel sea is a zone where the interplay between these various levels becomes a sensitive issue. The wreck of the Erika accelerated the reinforcement of security measures. A series of proposals, the Erika I and Erika II packages dealing with the control of ports, activities, and a programme for the elimination of single-hulled oil tankers has been made to member states. A European Maritime Security Agency was created in 2002, to give technical support to the Commission and states for improvements in maritime security.

The United Kingdom and France have coordinated their various statutes. It is now normal for the maritime security authorities of both countries to call on each other, to intervene in each other’s territorial waters when necessary. The personnel of the surveillance centres, such as at Dover and Gris-Nez, attend training sessions at one another’s premises. Competence in safety measures resides at both national and European levels. The regional and local authorities, which find themselves in the front line of risk management and responsibility for following up accidents, are attempting to find their place in a better organised prevention and intervention service. Inter-state coordination has evolved significantly, and the level of technical support, and the capacity of national institutions to intervene have improved. The framework provided by the European Union is still embryonic, and the role of regional and local stakeholders even more so. Without doubt this is one area of governance in the Channel area that is open to further development.

The gathering of information relating to traffic, its quality and its exchange, and the improvement of systems facilitating decision-making and intervention, are just as essential for the safety of large vessel traffic as for fishing and leisure craft. Initial progress in the national and European programmes (Safeseanet), are a demonstration of anticipated future benefits. The chain of intervention needs to involve local and regional stakeholders, state bodies and the European Union in perfecting information systems, and in the multiple training programmes of all those charged with accident prevention on a daily basis, from ships’ personnel to surveillance officers on land. If then, the Channel could describe itself as being not only the world’s busiest, but also the world’s safest sea, it would be no mean accomplishment.

top