Shared Histories

Shared Histories

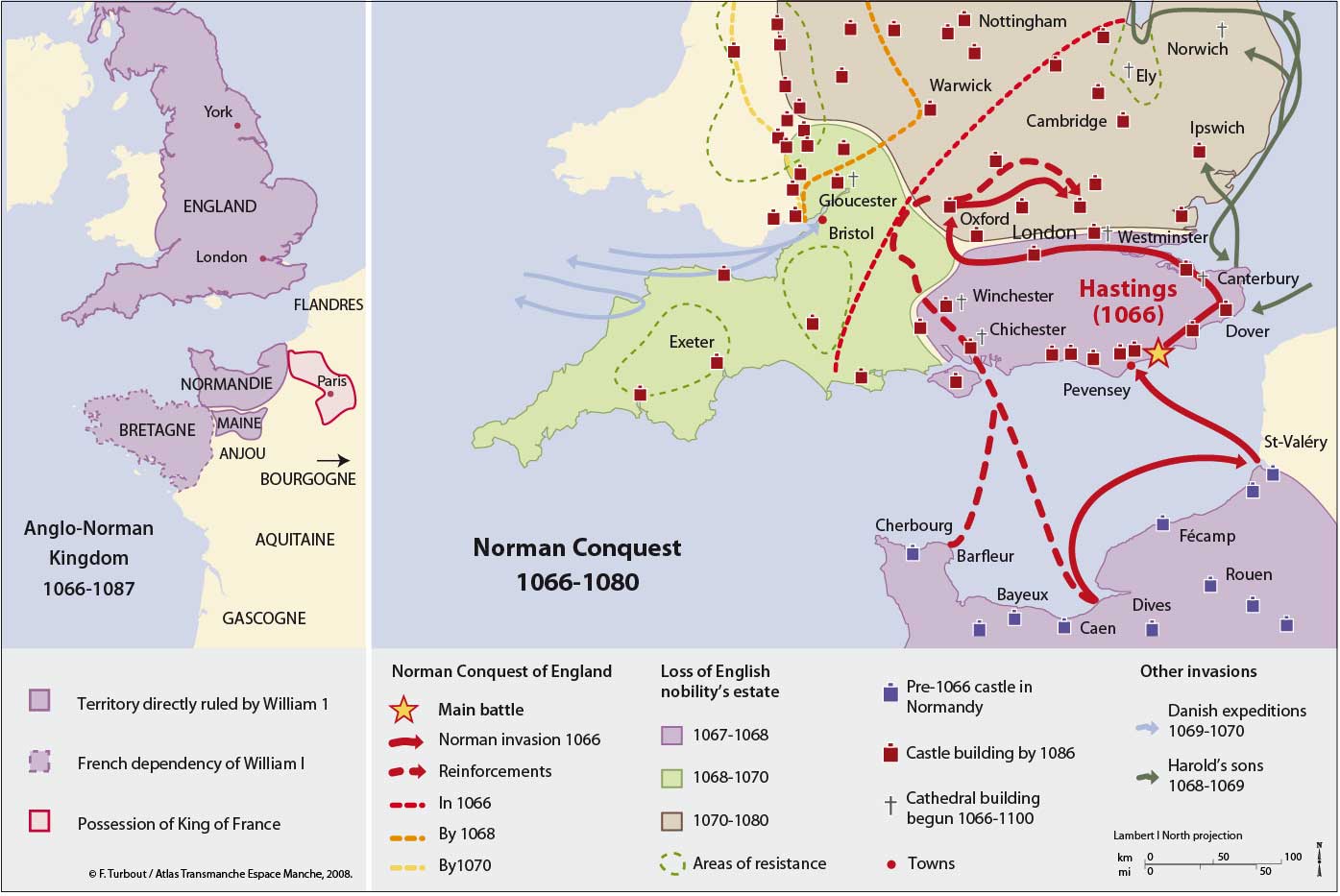

The Battle of Hastings on 14th October 1066 settled the fate of an entire ruling class, but it took 20 years to suppress internal resistance and invasions from outside. A massive programme of castle building was vital to the completion of the Conquest and, as the Normans tightened their grip on England, there was a parallel dispossession of the landowning “Anglo-Saxon” nobility. The Normans of the 11th century, unlike their Viking ancestors, had integrated with the existing Frankish post-Carolingian civilisation. Devoutly Christian, enthusiastic builders of churches and monasteries, their Norman Romanesque style had already influenced English church architecture before the Conquest. The joint Anglo-Norman kingdom not surprisingly generated a considerable amount of cross-channel “ferry” traffic. French remained the language of the court until the 15th century when Henry IV (1399-1413) became the first King whose mother tongue was English.

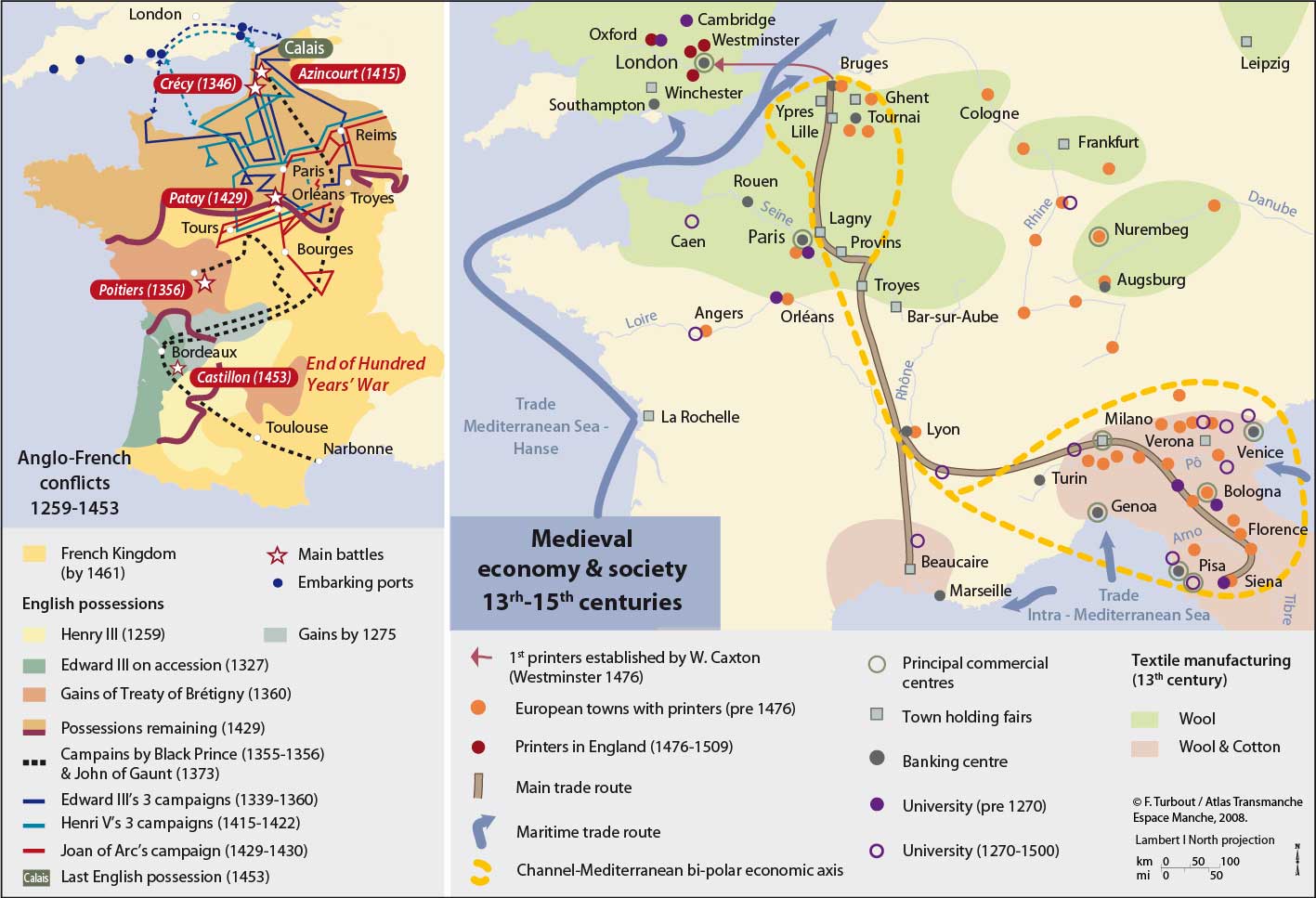

The institutional strength of feudal monarchies developed during the 12th century, with royal authority in both England and France both strengthened and extended over their respective domains. With the Plantagenet expansion (1128-1189), the Angevin Empire (1154 - early 13th) and England’s growing territorial ambitions in France, the scene was set for a struggle. Henry II’s acquisition of the Duchy of Guyenne through his marriage to Eleanor of Aquitaine would ultimately lead to the “Hundred Years’ War” (1337-1453). By then, cross-Channel raids from both sides had become almost a way of life. In 1338, Southampton was sacked by the French with the help of the pirate Grimaldi; in 1410 Fécamp was burnt down by the English. Continuing attacks did not prevent maritime links from continuing to prosper. England and France were emerging as autonomous and self-contained kingdoms.

More generally, Western Europe was undergoing a series of profound material and social changes, with a dramatic rise in agricultural production sustained by strong population growth.

top